How to Analyze a Cash Flow Statement: Guide for Indian Investors

Master cash flow statement analysis with a step-by-step guide for Indian stock investors. Link CFO/OCF, capex and free cash flow to spot high-quality stocks.

If the Profit & Loss (P&L) statement is a company’s resume, the Cash Flow Statement (CFS) is its bank statement.

Most Indian investors spend hours tracking stock prices, reading news, and calculating ratios—yet they ignore the one financial statement that reveals the truth about a business: the Cash Flow Statement.

Here’s the reality:

Profits can be manipulated. Cash is harder to fake.

This comprehensive guide explains how stock investors should read and analyze cash flow statements in practice—not as theory, but as a truth detection system for allocating capital in Indian listed companies.

⚠️ Critical Caveat: Not for Banks & NBFCs

This framework applies to non-financial companies only (manufacturing, services, IT, consumer, pharma, industrials, etc.).

Do NOT apply this analysis to banks, NBFCs, insurance companies, or financial institutions, where cash flows behave entirely differently.

Why? For a manufacturing company, cash is the result of business. For a bank, cash is the raw material. A bank showing negative operating cash flow is often growing aggressively, which can be good.

For financials, focus on: Asset quality (Gross NPA, Net NPA), credit growth trends, Net Interest Margins (NIMs), Provision Coverage Ratio, and Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR).

1. Why Cash Flow Analysis Matters More Than Profits

In the Indian stock market, you’ll find many companies that show:

Growing profits year after year

Rising EPS and attractive PE ratios

Impressive EBITDA margins

“Record Performance” press releases

Yet these same companies:

Continuously raise debt to survive

Struggle to pay dividends consistently

Keep diluting equity through rights issues

Face sudden liquidity crises

Eventually crash despite “strong fundamentals”

Why does this happen?

Because accounting profits never converted into actual cash.

As a stock investor, your fundamental question should never be:

“Is the company profitable?”

Instead, ask:

“Is the business actually generating cash that can reward shareholders?”

This is where cash flow analysis becomes non-negotiable.

2. The Financial Statement “Medical Checkup” Framework

Before diving into cash flow analysis, understand how the three financial statements work together.

Think of the three statements as a comprehensive medical checkup:

P&L Statement (Profit & Loss): The patient says, “I feel great, I’m strong” → Shows Performance

Balance Sheet: The doctor measures muscle and fat → Shows Health & Strength

Cash Flow Statement: The blood test showing oxygen levels → Shows Vitality

As an investor, your job is to triangulate. You must cross-check what the P&L claims against what the Balance Sheet and Cash Flow Statement reveal.

If these stories don’t match, the company is lying.

This guide will teach you exactly how to perform this triangulation.

3. The 3 Buckets — Understanding Cash Flow Components

A cash flow statement has three components:

Cash Flow from Operations (CFO) — Cash from core business

Cash Flow from Investing (CFI) — Cash used for growth/assets

Cash Flow from Financing (CFF) — Cash from/to lenders and shareholders

Accountants read all three equally.

Investors do not.

Every company sorts its cash movements into these three buckets. As an investor, you are looking for a specific “quality pattern”.

3.1 Operating Cash Flow (CFO): The Engine

What OCF Really Tells You

Operating Cash Flow (also called CFO) shows cash generated from core business operations—the actual money coming in from selling products or services.

This represents cash generated from the actual business (selling soap, software, or cars).

The Goal: You want Positive (+) and Growing CFO.

The Logic: If this is negative, the company is bleeding money to keep the lights on. It doesn’t matter what the “Net Profit” says; if CFO is negative, the business model is currently broken.

For investors, OCF answers the critical question:

“Is the company’s business model actually working in real money terms, or just on paper?”

Practical OCF Analysis Checks

Check #1: OCF vs PAT — The “Paper Profits” Test (Most Important)

This is the single most common place where Indian companies manipulate numbers.

Over a 3-5 year period, Operating Cash Flow should broadly track Profit After Tax (PAT).

Occasional year-to-year mismatch is acceptable

Persistent mismatch is a major red flag

How it works: A company can record a sale (and show profit in P&L) without actually receiving the cash.

The Check:

Compare EBITDA or PAT from P&L with Operating Cash Flow from CFS over a 3-5 year period.

The Logic:

If a company reports ₹1,000 Cr cumulative profit over 5 years, at least ₹700-800 Cr should have entered the bank as Operating Cash Flow.

Common Red Flag Pattern in Indian Markets:

P&L: PAT growing consistently every year, record high profits

Cash Flow Statement: OCF remaining flat or turning negative

This usually indicates:

Aggressive revenue recognition practices

Rising trade receivables (customers not paying)

Inventory piling up in warehouses

Working capital being used to “fund” growth

Investor Rule of Thumb:

Over a 3–5 year period:

Cumulative OCF should be at least 70-80% of Cumulative PAT

If cumulative OCF is significantly lower than cumulative PAT, dig deeper immediately.

Verdict: These are “paper profits.” The company is struggling to collect cash from customers, or revenue recognition is aggressive.

Investor Action: Avoid or investigate deeply.

Check #2: Working Capital Behavior

Many fundamentally decent Indian companies burn cash not because their business is bad—but because working capital is chronically mismanaged.

Watch for:

Sharp, unexplained rise in trade receivables

Inventory growing much faster than sales

OCF swinging wildly from positive to negative each year

Key Questions to Ask:

Is growth being “funded” by customers delaying payments?

Is the company aggressively pushing sales at quarter-end to meet targets, sacrificing cash collection?

Are distributors being stuffed with inventory?

Consistent working capital issues signal deeper problems with business quality or management discipline.

Check #3: One-Time Cash vs Sustainable Cash Generation

Do not get excited by:

A single year of exceptionally strong OCF

Temporary working capital release (one-time receivables collection)

Sale of scrap or one-off asset monetization

Always verify:

Is OCF improving consistently over multiple years?

Is the cash generation sustainable and repeatable?

Consistency and sustainability matter far more than one spectacular year.

3.2 Investing Cash Flow (CFI): The Future — Smart Growth or Wasteful Spending?

What Negative CFI Actually Means

Investing Cash Flow reveals where the company is deploying cash—typically in growth initiatives, capex, or acquisitions.

This shows money spent on buying assets (factories, machines) or parked in investments.

Most retail investors completely misread this section.

Negative investing cash flow typically indicates:

Capex on plant, machinery, technology, infrastructure

Strategic acquisitions

Capacity expansion or modernization

The Goal: Generally Negative (-).

The Logic: A negative number means the company is spending money to expand capacity (Capex). This is a sign of confidence in future growth.

Negative CFI is NOT automatically bad.

In fact, for growing companies, you want to see negative CFI—it means they’re investing for future growth.

Warning: If CFI is Positive, check why. Is the company selling off its land or factories just to pay salaries? That is a sign of distress.

The real investor question is:

“Is this capital investment creating future cash flows and returns?”

Practical CFI Analysis Questions

Ask yourself:

Is capex proportional to revenue growth? (Capex-to-sales ratio)

Are margins improving after heavy capex cycles?

Is Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) improving over time?

Major Red Flag Pattern:

Heavy, sustained capex year after year

No meaningful improvement in sales or margins

ROCE trending downward or stagnant

This pattern suggests poor capital allocation by management—they’re spending money without generating returns. This destroys shareholder value over time.

3.3 Financing Cash Flow (CFF): The Funding — Who’s Paying for Growth?

Financing Cash Flow reveals:

Debt raised or repaid

Equity dilution (share issuances)

Dividends and buybacks

This shows transactions with lenders and shareholders.

The Goal: Generally Negative (-).

The Logic: A negative number means the company is repaying loans or paying you dividends.

This section tells you who is actually funding the business—shareholders, lenders, or the business itself.

Critical Financing Cash Flow Signals

Signal #1: Debt Dependency Pattern — The “Ponzi” Warning

If you consistently see:

Negative OCF (business not generating cash)

Negative CFI (spending on assets)

Positive financing cash flow (raising debt/equity)

It means:

The business is running entirely on borrowed money.

Warning: If CFF is consistently Positive, the company is surviving on “ventilator support” (constantly borrowing or diluting equity).

This is acceptable only temporarily during genuine growth phases.

Long-term reliance on external funding without OCF improvement is extremely dangerous.

Signal #2: The “Dividend via Debt” Scheme

Many Indian retail investors love high-dividend stocks.

But always verify:

Is dividend being paid from operating cash flow, or

Is it being paid from fresh borrowings?

The Scenario: The company pays a fat dividend (CFF outflow) but simultaneously raises new debt (CFF inflow).

The Analysis: They are borrowing money to pay dividends to keep the stock price up.

How to check:

Look at the same year’s OCF. If OCF is negative or barely positive, yet dividends are substantial, the company is borrowing to pay dividends.

Dividends funded by debt are completely unsustainable and signal deeper cash problems. This is Ponzi-like behavior. A company should pay dividends from Operating Cash, not from Bank Loans.

4. Free Cash Flow (FCF): The Holy Grail — The Ultimate Investor Metric

Here’s the single most important metric for equity investors:

Free Cash Flow (FCF) = Operating Cash Flow (CFO) – Capital Expenditure (Capex)

This is the cash left for you after the company maintains its assets.

Free Cash Flow represents the cash that:

Can be used to repay debt

Pay sustainable dividends

Fund share buybacks

Acquire other businesses

Create actual shareholder value

How to Interpret FCF as an Investor

Consistent positive FCF → Strong, cash-generative business model

Negative FCF during expansion phase → Acceptable if ROCE is improving

Chronic negative FCF with no growth → Serious warning sign, avoid

Avoid: “Capital Guzzlers”—companies that earn ₹100 but must spend ₹120 on new machines just to survive (common in Telecom/Airlines).

Historical Pattern:

Many Indian multibagger stocks showed consistently strong and growing Free Cash Flow years before the broader market discovered them.

FCF is often the “early warning signal” of quality.

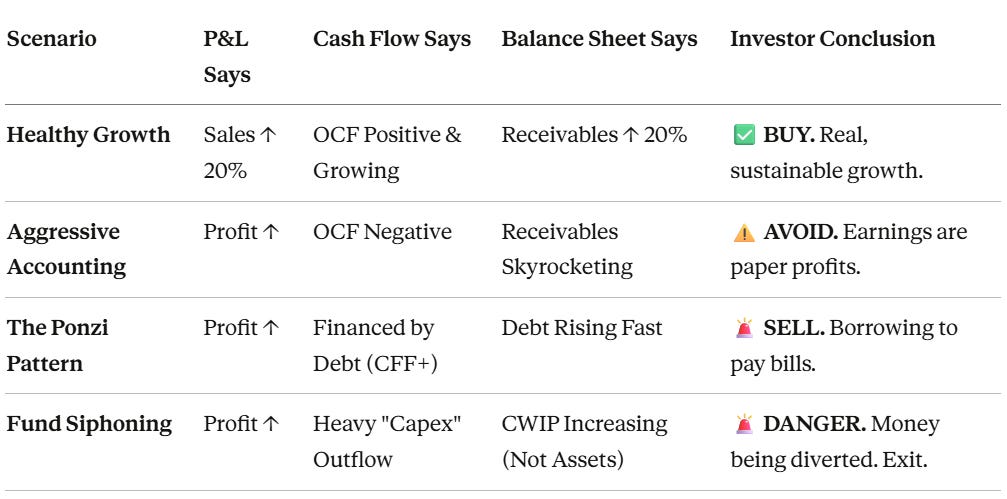

5. Advanced Investor Section — The 4 Critical Cross-Statement Links

Now we move beyond standalone cash flow analysis to cross-statement triangulation—where you catch manipulation and fraud.

If you want to go beyond surface-level analysis, this is how experienced investors catch accounting stress early.

These four links will help you detect if a company is doctoring its numbers.

5.1 The “Profit vs Cash” Reality Check

Connects: P&L (Net Profit) ↔ Cash Flow Statement (Operating Cash Flow)

This is the single most common place where Indian companies manipulate numbers.

How it works:

A company can record a sale (and show profit in P&L) without actually receiving the cash.

In India, “cooking the books” often happens by inflating sales that never result in cash.

The Check:

Compare EBITDA or PAT from P&L with Operating Cash Flow from CFS over a 3-5 year period.

The Logic:

If a company reports ₹1,000 Cr cumulative profit over 5 years, at least ₹700-800 Cr should have entered the bank as Operating Cash Flow.

The Rule: Total CFO should be at least 70-80% of Total EBITDA or PAT.

Red Flag Example:

P&L: Record high profits year after year

Cash Flow Statement: Zero or negative Operating Cash Flow

If a company reports ₹500 Cr EBITDA but only ₹50 Cr CFO, stay away.

Verdict: These are “paper profits.” The company is struggling to collect cash from customers, or revenue recognition is aggressive. The profits are likely fake or stuck in “Receivables” (customers who haven’t paid).

Investor Action: Avoid or investigate deeply.

5.2: The “Sales vs Receivables” Check — The “Channel Stuffing” Test

Connects: P&L (Revenue) ↔ Balance Sheet (Trade Receivables)

This tells you if growth is real or artificially forced through channel stuffing.

The Check:

Compare the Growth Rate (%) of Sales vs Growth Rate (%) of Trade Receivables.

The Logic:

If sales grow by 15%, receivables should ideally grow by roughly 15% as well—assuming consistent payment terms.

Red Flag Example:

P&L: Sales up 15% YoY (looks great!)

Balance Sheet: Trade Receivables up 50% YoY (wait, what?)

Verdict: This is “Channel Stuffing”—the company is dumping products on distributors just to hit sales targets before year-end. Distributors haven’t sold the products yet, so cash doesn’t come in.

The company is “stuffing the channel”—forcing distributors to take goods on credit just to show higher Sales numbers.

This practice typically collapses within 1-2 years when distributors stop accepting more inventory.

Investor Action: Major red flag. Avoid.

5.3: The “Debt vs Interest” Check

Connects: Balance Sheet (Borrowings) ↔ P&L (Finance Cost)

This reveals if the company is hiding its true cost of borrowing to artificially inflate profits.

The Check:

Calculate the Implied Interest Rate:

Formula:

Implied Interest Rate = (Finance Cost / Total Debt) × 100

The Logic:

Compare this rate with prevailing market rates. If the company is rated ‘A’ or ‘AA’, it should be paying roughly 8-12% interest in the current Indian market.

Red Flag Example:

Balance Sheet: Total Debt = ₹1,000 Cr

P&L: Finance Cost (Interest) = ₹10 Cr

Implied Interest Rate = 1%

Verdict: Impossible. Where is the remaining ₹80-100 Cr of interest expense?

The Common Trick:

The company is “capitalizing interest”—adding interest expense to “Capital Work in Progress (CWIP)” on the Balance Sheet instead of expensing it on the P&L.

This artificially inflates reported profits while hiding true interest burden.

Investor Action: Deep governance concern. Investigate or avoid.

5.4: The “Investment vs Asset” Check — The “Fake Factory” Trap

Connects: Cash Flow Statement (Capex) ↔ Balance Sheet (Fixed Assets) ↔ P&L (Depreciation)

This checks if the company is actually building the factories and assets it claims to be building, or siphoning money out.

The Check:

Follow the money trail across all three statements:

Cash Flow Statement: You see an outflow called “Purchase of Fixed Assets” (Capex)

Balance Sheet: You should see “Gross Block” (Fixed Assets) increase by roughly the same amount

P&L: You should see “Depreciation” increase proportionally (more assets = more depreciation)

Red Flag Example:

Cash Flow Statement: Huge capex outflow (₹500 Cr spent)

Balance Sheet: Fixed Assets (Gross Block) barely increased; instead, “Capital Work in Progress (CWIP)” skyrocketed by ₹500 Cr

P&L: Depreciation remains flat

Verdict: The “capex” might be fake or diverted.

Money is leaving the company under the guise of “building a factory,” but the factory never gets completed—it stays in CWIP forever. This is a common method for fund siphoning in India.

The Scam: In India, dodgy promoters often siphon money out by claiming they are building a factory, but the money sits in CWIP for 5-10 years and the factory is never finished.

Investor Action: Extreme red flag. Likely fraud. Avoid completely.

6. The “All-in-One” Consistency Test: Reserves & Surplus

If you want a quick, powerful way to link all three statements without complex calculations, examine the Reserves & Surplus line on the Balance Sheet.

How It Works:

The flow should work as follows:

Opening Reserves & Surplus (Balance Sheet)

+ Net Profit for the year (P&L)

- Dividends Paid (Cash Flow Statement)

= Closing Reserves & Surplus (Balance Sheet)

The Check:

Does this equation balance out? Does the math work out?

Red Flag:

If Closing Reserves are significantly lower than what the equation suggests, money has leaked out of the company unaccounted for.

This could indicate:

Undisclosed write-offs

Hidden related-party transactions

Fund diversion

Governance fraud

Investor Action: Massive governance red flag. Exit immediately.

7. Advanced Metrics for the Smart Investor

Related Party Transactions: The “Indian” Risk

Open the detailed Cash Flow Statement in the Annual Report. Look under Cash Flow from Investing.

Look for: “Loans given to related parties” or “Inter-corporate deposits.”

The Risk: Promoters often move cash from the listed company (where you own shares) to their private unlisted firms.

Verdict: If a company is making cash but lending it to the Promoter’s other companies instead of paying dividends, run away.

8. Common Cash Flow Traps in Indian Stock Market

Watch out for these patterns repeatedly seen in Indian equities:

Trap #1: PAT Growth Driven by Receivables

Profits growing, but entirely due to customers not paying on time

Receivables ballooning quarter after quarter

Company keeps giving “temporary working capital” excuses

Trap #2: EBITDA Growth Without OCF Growth

EBITDA looks impressive

Operating Cash Flow is stagnant or negative

The “growth” exists only on paper

Trap #3: “Adjusted” Cash Flow Explanations

Management constantly provides elaborate “adjusted cash flow” explanations

They blame “one-time” working capital issues every single year

Excuses change, but cash problems persist

Investor Rule:

If excuses repeat year after year, the problem is structural, not temporary.

9. Summary Table: Linking All Three Statements

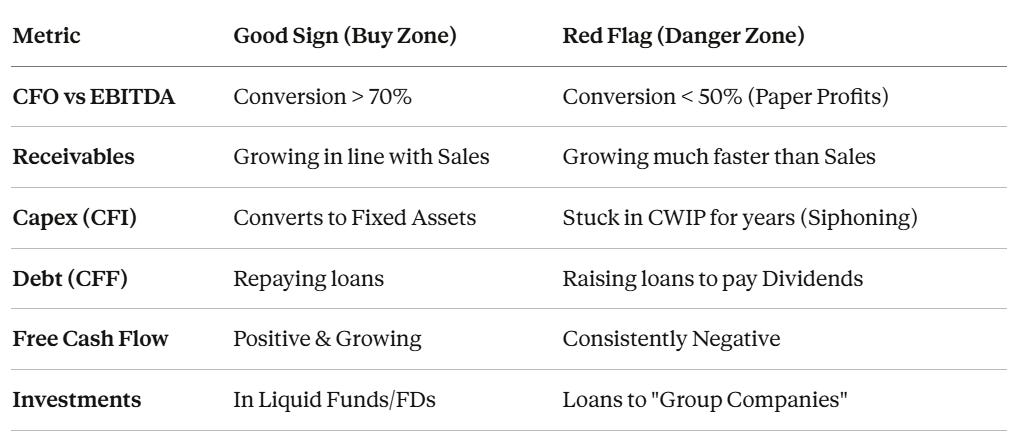

10. Final Investor Checklist: Save & Use This

Before investing in any Indian listed company, ask yourself:

Operating Cash Flow:

[ ] Is operating cash flow consistent with reported profits over 3-5 years?

[ ] Is cumulative OCF at least 70-80% of cumulative PAT?

[ ] Is working capital under control (receivables, inventory)?

Cross-Statement Links:

[ ] Does sales growth match receivables growth?

[ ] Does implied interest rate make sense given debt levels?

[ ] Is capex actually showing up as fixed assets on balance sheet?

[ ] Does the Reserves & Surplus equation balance out?

Investing & Financing:

[ ] Is capex generating improving returns (ROCE trending up)?

[ ] Is growth funded by cash generation or continuous borrowing?

[ ] Are dividends paid from OCF or from fresh debt?

Free Cash Flow:

[ ] Is Free Cash Flow (OCF - Capex) positive and improving over time?

[ ] Can the business sustain itself without external funding?

Advanced Checks:

[ ] Are there suspicious loans to related parties?

[ ] Is CWIP growing without converting to fixed assets?

[ ] Is interest being capitalized instead of expensed?

If you answer YES to most of these questions, the business is likely fundamentally sound.

If you see multiple red flags, walk away—there are thousands of other investment opportunities.

10.1 Quick Reference: Summary Checklist

11. Closing Thought: The Investor’s Truth Detector

As a stock investor in India, you don’t get paid for accounting profits shown in press releases.

You get paid when:

Cash flows grow consistently

Capital is allocated intelligently

Market eventually recognizes quality and re-rates the stock

The P&L is the promise.

The Balance Sheet is the proof.

The Cash Flow Statement is the payment.

Never trust the promise without verifying the proof and the payment.

Learn to read the cash flow statement—not as accounting theory, but as a truth detection system that protects your capital and identifies genuine wealth-creating businesses.

Master this skill, and you’ll avoid 80% of the value traps and accounting frauds that plague the Indian stock market.

Don’t like what you are reading? Will do better. Let us know at hi@moneymuscle.in

Don’t miss reading our Disclaimer

Awesome . Keep up the good work

Brillian breakdown on the OCF-to-PAT conversion check. The 70-80% threshold over 3-5 years is somthing I wish I knew earlier when I got burned by a stock showing "record profits" that never turned into actual cash. The cross-statement triangulation approach basically turns the three financials into a lie detector test, which is exactly what retail investors need in a market where promoters get creative with accounting. One question though: for companies in hyper-growth mode with genuinely expanding working capital needs, how do you differentiate between temporary cash drag and structural manipulation?